First, some history. If you don’t like reading about it just skip to the ruler below.

So, NAScale is born after yet another attempt to design a good colourspace conversion and scaling library. Long time ago FFmpeg didn’t have any proper solution for that and used rather rudimentary imgconvert; later it was replaced with libswscale lifted from MPlayer. Unfortunately it was designed for rather specific player tasks (mostly converting YUV to RGB for displaying with X11 DGA driver) rather than generic utility library and some of its original design still shows to this day. Actually, libswscale should have a warm place in every true FFmpeg developer’s heart next to MPEGEncContext. Still, while being far from ideal it has SIMD optimisations and it works, so it’s still being used.

And yet some people unsatisfied with it decided to write a replacement from scratch. Originally AVScale (a Libav™ project) was supposed to be designed during coding sprint in Summer 2014. And of course nothing substantial came out of it.

Then I proposed my vision how it should work and even wrote a proof of concept (i.e. throwaway) code to demonstrate it back in Autumn 2014. I’d made an update to it in March 2015 to show how to work with high bitdepth formats but nobody has touched it since then (and hardly before that too). Thus I’m reusing that failing effort as NAScale for NihAV.

And now about the NAScale design.

The main guiding rule was: “see libswscale? Don’t do it like this.”

First, I really hate long enums and dislike API/ABI breaks. So NAScale should have stable interface and no enumeration of known pixel formats. What should it have instead? Pixel format description that should be good enough to make NAScale convert even formats it had no idea about (like BARG5156 to YUV412).

So what should such description have? Colourspace information (RGB/YUV/XYZ/whatever, gamma, transfer function etc), size of whole packed pixel where applicable (i.e. not for planar formats) and individual component information. That component information includes information on how to find and/or extract such component (i.e. on which plane it is located, what shift and mask is needed to extract it from packed bitfield, how many bytes to skip to find the first and next component etc.) and subsampling information. The names chosen for those descriptors were Formaton and Chromaton (for rather obvious reasons).

Second, the way NAScale processes data. As I remember it libswscale converted input into YUV with fixed precision before scaling and then back into destination format unless it was common case format conversion without scaling (and then some bypass hacks were employed like plane repacking function and such).

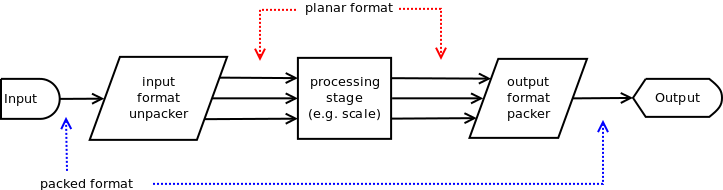

NAScale prefers to build filter chain in stages. Each stage has either one function processing all components or a function processing only one component applied to each component — that allows you to execute e.g. scaling in parallel. It also allows to build proper conversion+scaling process without horrible hacks. Each stage might have its own temporary buffers that will be used for output (and fed to the next stage).

You need to convert XYZ to YUV? First you unpack XYZ into planar RGB (stage 1), then scale it (stage 2) and then convert it to YUV (stage 3). NAScale constructs chain by searching for kernels that can do the work (e.g. convert input into some intermediate format or pack planes into output format), provides that kernel with a Formaton and dimensions and that kernels sets stage processing functions. For example, the first stage of RGB to YUV is unpacking RGB data, thus NAScale searches for the kernel called rgbunp, which sets stage processing function and allocated RGB plane buffers, then the kernel called rgb2yuv will convert and pack RGB data from the planes into YUV.

And last, implementation. I’ve written some sample code that would be able to take RGB input (high bitdepth was supported too), scale it if needed and pack back into RGB or convert into YUV depending on what was requested. So test program converted raw r210 frame into r10k or input PPM into PPM or PGMYUV with scaling. I think it’s enough to demonstrate how the concept works. Sadly nobody has picked this work (and you know whom I blame for that; oh, and koda — he wanted to be mentioned too).